Last updated: May 2018

When we enter the world of aromatic plants, essential oils and aromatherapy, we’re usually all excited and pumped up to try everything. But it is precisely this phase of initial enthusiasm that may pose a threat. We can quickly misinterpret things or start following wrong or even dangerous advice, ending up doing more damage than good.

As a beginner, how can you recognise good and bad practices from a jumble of internet sources, books, friends, aromatherapists? What details should you pay attention to when discovering a new source of essential oil information, and which claims should set alarm bells ringing?

How can you know who is trustworthy and whom to avoid in a big circle?

In the beginning, things can look very confusing. People make all sorts of claims that may seem odd or contradict what others say, and you can quickly end up in an information overload.

I always recommend learning the basics before you start using essential oils: what essential oils are and what they are not, how they are produced, when is it justifiable to use them and when it is not, which ones are most suitable for home use and which you should avoid, and general safety measures. When familiar with the basics, everything will be much easier.

While differentiating between reliable and less reliable sources requires knowledge and experience, eliminating useless, misguided or even dangerous advice is relatively easy.

In the following, I will describe some key points that you can use to orient yourself and eliminate questionable sources even if you don’t have any experience. We can separate those key points into two groups: to the first group belong those concerning plants and essential oils as such and to the second one those relating to the use of essential oils and aromatherapy in general.

NOTE: The mentioned signs, phrases or recommendations have orientation purpose and mark only the most obvious criteria for identifying suspicious information sources. You should have in mind that we all continuously learn and make mistakes, and a lapse here and there does not necessarily mean that the source or a person behind it is unreliable. Moreover, new data about essential oils and their use is emerging fast, which means that something that held true yesterday may turn out to be incomplete or even wrong today. So check out multiple signs before deciding whether you trust someone or not.

1. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT ESSENTIAL OILS AND PLANTS

- Is there a definition of essential oils and is it accurate?

Essential oils aren’t any life force, they don’t circulate in plants like blood or even carry oxygen and nutrients, and thus aren’t any circulatory or immune system analogue of plants. If you see such claims your alarm bells should be ringing.

Read more about essential oil definitions and how they differ from the plant volatiles.

- Not all aromatic extracts are essential oils

There’s no essential oil of jasmine, violet, honeysuckle, osmanthus, tuberose or carnation, and neither are there essential oils from animals. If it’s obvious that an author doesn’t discriminate between essential oils and solvent extracts (such as absolutes, supercritical (CO2) extracts, tinctures, etc.), this indicates the lack of the most basic knowledge about essential oils.

A particular part of the story is not distinguishing between essential oils and fatty plant oils. I heard about the peanut essential oil, for example. Essential oils aren’t technically oils. Generally, they don’t contain lipids, such as triglycerides (fats), waxes or sterols, although some contain very small amounts of fatty acids, a type of lipid. Essential oils are predominantly composed of terpenes and phenylpropanoids, and their derivatives.

- Not distinguishing between natural extracts and perfume oils

Essential oils of peach, apple, strawberry and other fleshy fruits don’t exist. Their fragrances are sold as perfume oils, reconstitutions of natural fragrances using synthetically manufactured aroma chemicals, which also comprise a significant part in the majority of modern perfumes.

In recent years, however, natural extracts of certain fruits appeared on the market in the form of supercritical (CO2) extracts, or as mixtures of natural isolates. Natural isolates are single compounds obtained from plant extracts by a process called fractionation. That’s why reconstitutions from natural isolates can be marketed as natural products and used in natural cosmetics, even though coming from many different plants that may have nothing in common with the plant whose fragrance they’re used to reconstitute.

- Are the botanical (Latin) names stated?

If a source is supposed to be an expert or a professional one, botanical naming is the standard. Clary sage and common sage, Roman chamomile and German chamomile, sweet basil and holy basil can differ substantially in their volatile composition and safety measures.

Botanical naming is the most precise and internationally accepted way of classifying plants; not employing it is not a good sign.

On the other hand, it’s useful if you get familiar with the botanical names, if only just a few basic ones. Searching for information using the botanical names will significantly boost the likelihood of finding higher quality results.

- Claims that essential oils were used by the Ancient Egyptians and/or mentioned in the Bible

Yet another type of claims with no scientific evidence, sometimes reaching unbelievable proportions. Essential oils as we know them today have existed for about 1000 years (though some new but inconclusive evidence points in another direction, but that’s another story).

The oils mentioned in ancient texts were most likely herb and resin infused oils, not essential oils. When writing about the supposed ancient use of essential oils, authors frequently use just “oils”, omitting (on purpose?) the “essential” part. Such hiding behind unspecific terms is all over the place in many generic articles, listicles and infographics (see next bullet). You can check out for yourself how many essential oils does the Bible actually mention 🙂

Let’s move on to some less obvious, but more significant points.

- Equating beneficial effects of essential oil with herbs

This is likely the most widespread misassumption that is unique to aromatherapy. It started at least 400 years ago (but probably much earlier) when leading herbalists were incorporating distilled plant products into their medical practice (e.g., Culpepper 1652). Of course, nothing was known at the time about the chemistry of medicinal plants.

However, this generalisation continued in the 20th Century when early aromatherapists drew their knowledge mainly from herbal books. And sadly, it remains widely present in many of today’s popular aromatherapeutic books and online sources.

Although essential oils are highly concentrated, their composition represents only the volatile part of plants’ secondary metabolite profile. It is estimated that of all known secondary metabolites, volatiles present roughly about 1% (Dudareva et al. 2006).

In the majority of medicinal plants, known beneficial effects are due to non-volatile compounds, such as alkaloids, tannins, carotenoids, bitters, mucilages, flavonoids, saponins and vitamins. Aromatherapy is only a small and specific subset of more general phytotherapy.

Essential oils, for example, cannot have astringent effects because they don’t contain tannins. Distillates from St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum) won’t have antidepressive activity as they don’t contain hypericin and hyperforin. Frankincense (Boswellia sp.) essential oils won’t contain anti-tumorigenic boswellic acids, and there will be no cannabinoids (such as THC and CBD) in the cannabis distillates. There’s much more to this – in fact, this misconception is so huge that it undermines the credibility of aromatherapy as a whole.

Is there a way to recognise this bad practice? Well, it’s difficult if you don’t know what to look for, but listing all sorts of healing effects without citing the relevant research (see next bullet) is already a bad sign. If the original research is cited, you can google the headline and usually it is evident from the abstract whether the study was conducted on essential oils or solvent extracts. If it just says that ‘extracts’ from X plant were used, you can be quite sure there were no essential oils involved.

It is true that the majority of research is done on solvent extracts and single constituents, rather than essential oils. But this shouldn’t be the reason or an excuse to extrapolate those findings to essential oils.

- Is original research cited?

For general information about essential oils, citing original research is not necessary, but is indeed desired when making specific claims. Scientific literature is based on the empirical method (controlled conditions, precise measurements, sufficient sample size, reproducibility, statistics, peer review, etc.), and should thus be the primary source of essential oil information.

Citing original research not only lends credibility to claims that an author makes, but it’s also a fair way of making information transparent to the audience.

- Is the cited research interpreted correctly? (if you’re a beginner, you can skip this one)

It’s easy to search databases such as PubMed, Research Gate or Google Scholar to find scientific articles, books and other reports. There are thousands of published papers about essential oils and their constituents.

What matters is how the research is interpreted. Although it may be difficult to determine if the cited research is correctly interpreted or even relevant, you should at least be aware of potential traps.

1) Not all research is quality, especially nowadays when quantity is more important than quality. The internet is full of dubious “scientific” journals and publishers that will publish just about anything, as long as they collect their publishing fees. Bad research can be noticed from a mile away, but sometimes it requires careful reading throughout the article.

2) Incorrect interpretation of research results can happen when an author lacks sufficient background, reads just an abstract of a study, or is just sloppy. One of the most common examples of misinterpretation is an over-interpretation from in vitro (lab) studies to whole organisms. If a study finds that an essential oil or a single compound from that oil exhibits anti-tumorigenic potential on a human tumour cell line, this doesn’t mean it can actually cure cancers in humans.

Another frequent misinterpretation is taking individual claims out of context, such as “forgetting” to mention that a study was conducted on mice (thus implicitly suggesting that the results are proven for humans) or that results are valid only in certain conditions. Such claims can quickly mislead us. In most cases, high-quality clinical trials supported by relevant mechanistic studies are the final step in providing proof that something works for humans.

3) Cherry picking. Let’s say you read an online article citing a study A that confirms the hypothesis X. You will believe that claim, right? But what if there’s also a study B (and perhaps C) that rejects that hypothesis or is inconclusive about it, but is not mentioned in the article?

Which cherry will you pick?

You guessed it: it’s not good, it’s difficult to spot (unless you’re a specialist in a field) and it’s called cherry picking, or biased representation of data. There’s not much you can do about it, but bear in mind that nobody is entirely immune to it, including the researchers. In most cases, cherry picking is unintentional. Authors may simply find what they search for and cite it to back up their claims, without looking at the big picture.

- Claiming that home users can discern essential oil quality and purity based on GC–MS analysis

When it comes to quality of essential oils, you will sooner or later encounter the acronym GC–MS (Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry). It is the key analytical method, which enables us to see the detailed chemical composition of essential oils.

The goal of the GC–MS analysis is to explain as much essential oil composition as possible and to identify potential impurities. The end result is a list of constituents and their percentages, identified in a specific distillation batch of essential oil.

In recent years, an idea became popular that home users themselves can read from the GC–MS report if an essential oil is pure and of high quality. The idea is indeed attractive, but in reality, it’s not that easy. Unless your oil is poorly adulterated (with something that obviously shouldn’t be there) and you know what you’re looking for, it’s very difficult.

In most cases, essential oils are adulterated with nature-identical aroma chemicals, produced via organic synthesis. The process of manufacturing aroma chemicals always leaves certain impurities, which act as markers analysts are looking for when verifying authenticity. There are other methods, such as measurements of optical properties of the molecules, which can further inform the analyst whether synthetic adulterants were added.

Non-specialists do not have this information at hand and must, therefore, rely on professional analysts or trust the providers.

Can the GC–MS analysis tell you the quality of essential oil?

Assuming you have a pure and authentic oil, what is the measure of quality? Is it the diversity of the constituents? High levels of key constituents? Or rich and natural smell?

Well, it depends on whom you ask; there’s no right or wrong answer. Quality depends on what you’re planning to do with your oil. The GC–MS analysis can help you with that decision, but it does not, by itself, determine the quality of essential oils.

You can, however, use the report to calculate safe dilution rates for oils that contain toxic or irritable constituents (see next bullet) or to pick up essential oils with the highest levels of desired constituents.

2. INFORMATION ABOUT ESSENTIAL OIL USE

Now if we can pardon some incorrect information about essential oils since not every provider has a background in natural science, it is advisable to take a more critical stance towards various recommendations regarding their use. Let’s scroll through some key points that will help you determine whether the source is trustworthy or not.

- Advising topical use of undiluted essential oils

You probably know that essential oils are highly concentrated mixtures of compounds that may be irritable or toxic if used undiluted. As a rule of thumb, all essential oils must be diluted before application, especially if you’re not familiar with the particular oil. For a dermal application, typically 1-3% concentration is used, but safe dilution rate varies considerably, depending on the essential oil, type of application (massage or local targeted application), age and dose.

How can you find safe dilution rates for specific essential oils?

It’s always good to have an evidence based literature at hand, whether you’re new to essential oil use or an experienced user. A classic resource on safety guidelines is Robert Tisserand’s and Rodney Young’s Essential oil Safety (Second Edition from 2014). Although some resources may be a bit outdated, you will find lots of useful information about essential oils and individual constituents, with updated safety guidelines and regulations.

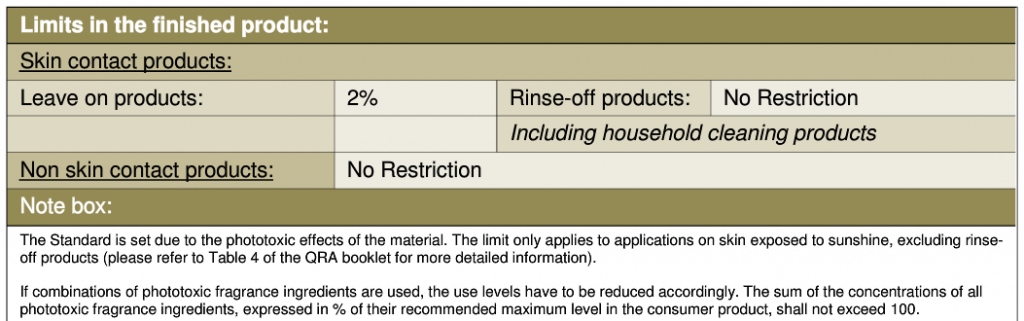

If you don’t have an appropriate book or want to have the newest guidelines, or you’re thinking of selling your products, you can look at the IFRA’s Standards page for consumer cosmetic products safety recommendations. Search under the “Standards library” and click “+” (this will show details) in the search results table. For example, if you type in “lemon” and click “+” at the “Lemon oil cold pressed” search result, you will see this:

This means that the maximum recommended level for the dermal application of the cold pressed lemon essential oil is 2% (on a weight-per-weight basis). You will also notice that this limit is due to known phototoxic compounds in that oil and that you should take into account their combined effect when using multiple phototoxic materials (expressed citrus oils except sweet orange oil, and some others such as angelica or cumin, are phototoxic).

Note however that only a few natural extracts are listed in the standards library, and you will likely have to search by individual toxic or sensitising constituents, which act as limiting substances. This makes sense as their quantities can vary significantly from batch to batch. For example, if your oil has 33% citral (geranial + neral) and the safety limit for citral is 0.6% for a leave-on topical application (Category 4), you should dilute to 100/33 = 3*0,6% = 1,8% max.

But how can you know which compounds are likely to be limiting for specific oils? Well, there’s no other way but to learn them.

Some common examples: carvone (spearmint), cinnamic aldehyde (cinnamon), citral (lemon balm, lemon grass, citronella, lemon tea tree, verbena…), citronellol (geranium), cuminaldehyde (cumin), estragol (tarragon, basil, star anise, fennel…), eugenol (clove), geraniol (geranium, thyme, palmarosa), octenyl acetate (lavender), methyl eugenol (rose, holy basil, pimento, bay leaf…), rose ketones (rose). This is by no means an exhaustive list!

- Advising the use of essential oils in water

Quite frequently we can encounter recommendations to add essential oil to a glass of drink. In this case, we’re dealing with the internal use of essential oils (see next bullet), as well as the use of undiluted essential oils.

Have a look at this advice:

A hint of mint? Well, if you try this (better not to) I can guarantee it won’t be a hint but a burning punch in your mouth. And what’s wrong with the mint leaves, anyway?

Water and essential oils don’t mix, regardless of the quantities used. You risk contact of an undiluted essential oil with mucus layers in the oral cavity, oesophagus and stomach, which can cause burns and inflammations.

The fact that essential oils and water don’t mix must also be taken into account when preparing aromatic baths.

- Advising the internal use of essential oils

The notorious internal use. In general and especially as a beginner you should avoid internal application of essential oils for any therapeutic purpose. It’s OK if you mix a drop of essential oil into a jar of honey to flavour it, but targeted internal use for therapeutic purposes usually consists of much higher doses and is limited to very specific cases.

Bear in mind that internal use doesn’t include only ingestion with oral capsules or direct ingestion together with food or drink, but also an application by rectal and vaginal suppositories. Application of aggressive essential oils on mucous surfaces such as oral cavity, vagina or rectum can cause serious burns and tissue necrosis when used in high concentrations, and local inflammations in prolonged exposures even when highly diluted (Endo and Rees 2007, Sarrami et al. 2002).

For some, ingesting essential oils is something progressive, as opposed to ‘old-school’ traditional thinking that is against internal use. I don’t see this as a traditionalist/progressionist issue because essential oils are extremely diverse; any generalisations on their activity and safety measures are simply misplaced. Each case needs to be assessed individually, and more safety data specific to internal use is generally needed.

In lay advice and coffee talks, internal use is often recommended for irrelevant, inappropriate or overly casual situations. For example, drinking water with lemon oil for more energy (where a better option would be to drink a glass of good old lemonade), treating vaginal infections with a tampon soaked in tea tree oil, or easing the teething pain with clove oil.

Another misleading claim comes from certain well-known providers, asserting that their essential oils are the only ones pure and therefore safe enough to be used internally. They may further justify this by pointing to other providers’ labels stating that essential oils are not intended for internal use.

It is indeed possible to register certain essential oils as a food supplement in some countries such as U.S. However, this does not depend on quality or purity of essential oils but on regularities under which they are registered (see next bullet). What matters the most is that essential oils’ safety does not depend on the producer, but on their chemical composition, application mode, dilution rate and dose.

- Labelling and marketing essential oils as therapeutic, medical, clinical and food grade

What exactly is the measure of therapeutic, medical, clinical grade? Who determines that?

As long as our essential oils are pure and authentic, they are suitable for therapy. Various labels, grades and fancy looking acronyms have nothing to do with actual therapeutic potential; they are just a marketing move. Don’t let them fool you.

There are of course some legitimate certificates such as those concerning growth standards (bio, organic, etc.), cultural standards (e.g., kosher) and certain international quality standards such as ISO or pharmacopoeias. The latter, however, define industry standards rather than therapeutic potential as such, and they apply only to a fraction of essential oils.

Certain essential oils have the GRAS status (meaning “generally recognised as safe”) which is approved by the FDA. Hence, they can be registered as food additives in the U.S. Again, the GRAS, or similar status in other countries, is not a quality or therapeutic grade, it just means that the material – a mixture or a single compound of natural or synthetic origin – is safe for its intended use as a food additive (flavoring) in very small amounts.

Check out this post about essential oil quality and certificates if you want to dig a bit deeper into this topic.

The bottom line is that there are no objective criteria for quality and no formal regulatory bodies for quality or therapeutic certification. Again, quality is a matter of context and depends on what we want to do with our essential oil.

- Employing functional groups to explain biological activity of essential oils

You may have encountered claims such as:

- To prepare a wake-up blend, choose essential oils high in alcohols

- Roman chamomile essential oil prevents spasms because it is rich in esters

- You should avoid using essential oils rich in ketones because they are neurotoxic

Well, I wish it were that easy! The functional group approach shows up in various forms, colours and sizes. Sometimes it’s hard to recognise as such because authors may not present it as a theory/hypothesis but simply take it as a fact. Whenever you encounter claims or graphical representations how essential oils are supposed to work in the body based on whole groups of molecules with similar properties, this is functional group theory.

I’ve written elsewhere extensively why the functional group theory is wrong. If you want to skip the details, the takeaway message is that this theory is only superficially scientific and has no real explanatory value. It’s one thing to classify essential oil constituents according to their chemical structure, which is fine (and it’s how you learn chemistry), but it’s something entirely different to attempt to explain extremely complex biological processes based on mere chemical classifications.

Biology is way more than chemical groups. The good news though is that you don’t need to be an expert in chemistry to know how to use essential oils.

- Recommending the use of essential oils for 1001 troubles

Essential oils certainly have proven biological and psychological effects, but they’re far from being a miracle solution to every problem. I’m frequently bewildered when reading through all sorts of indication lyrics, claiming that anything can be used to treat just about everything.

For example, listings of “27 reasons why you should use x oil” can be misleading because the majority of those reasons usually won’t have practical significance. You would either intoxicate yourself before some of the effects could even take place, or there are simply better solutions out there.

Be careful when encountering any big claims. Usually, it’s just a sign that someone wants to sell their products or give an impression of being an expert (see next bullet).

- Over-emphasising own expertise

This one can be rather tricky to notice by a beginner. Listing large numbers of beneficial effects, using unnecessarily difficult to understand, fancy-sounding terminology, citing a lot of poor or irrelevant research, offering definitive answers to complex problems, or continuously stressing one’s own experience in the field, should raise an eyebrow.

Learning how to tell apart talking smart and being smart is not easy. Try to read between the lines, don’t take what you read for granted – no matter where it comes from – and think rationally. Don’t let big claims and promises take over when deciding whom do you trust. Here’s a nice list of common logical fallacies, specifically relevant for aromatherapy; it’s an excellent exercise for developing critical thinking.

It’s quite funny actually when some people continuously underscore evidence-based approach but in the next moment say something esoteric or biologically nonsensical. This is not holism but mixing apples and oranges. Bear in mind that a true expert is very careful about the claims he or she makes, rather than acting like a know-it-all.

- Recommending the use of essential oils to treat diseases that need professional medical care

Take the amazing stories about almost miraculous healing that you read on facebook with a grain of salt. Even in cases that someone truly recovers from a severe condition, it’s very difficult to pinpoint the exact cause.

There’s no proof that essential oils can cure cancer or any other serious medical condition in humans. Following such advice can give you false hope, causing you to lose precious time when you could already be seeking professional help. Recommendations of this sort are not only dangerous but also unethical.

WHO IS THE SOURCE OF INFORMATION?

When separating the wheat from the chaff, it is useful to have in mind who is the source of essential oil information. We can divide them into 3 categories.

- Providers: online store owners, salespeople in specialised stores, or individual sellers and advocates that can be independent or belong to a multi-level marketing network.

- Educators: book authors, bloggers, presenters of webinars, workshops and courses.

- Producers: they often also sell essential oils directly to end users or act as educators (e.g., lead distillation workshops).

Depending on who is the information source, we can adjust our critical stance accordingly. From the producers we expect expertise in distillation techniques and procedures, but not a detailed theoretical knowledge about the chemistry of medicinal plants or essential oil safety. We are responsible for our own safety. The same applies to the sellers. Although we expect them to know their products, they may not be qualified to recommend their use, often relying on inaccurate sources or incidental cases.

As opposed to producers and retailers, you will typically aim to learn the most from the professional educators and therefore should be most critical about the information they provide. Keep in mind the key points described earlier. If the basic stuff doesn’t hold, what’s the chance that more specific topics will?

There is one more thing I would like to mention here: trusting your circle of people you know well can importantly affect how you will use your essential oils. Blind trust may not always be the best practice when attempting any serious use. Before taking advice, check out if recommended essential oils are suitable for your need in the first place, how to use them safely and what are the potential side effects.

WHERE TO START?

People often ask me where to start in all the jumble of information. The initial enthusiasm is usually a big enough motive to start educating yourself. But at the same time, it’s also a critical phase where you can make mistakes. Just start reading, eliminate dubious sources and don’t stick to a single source.

Education however never ends and the more you know, the more there is to learn. You will soon realise: there are no final answers! There’s much more about essential oils we don’t know about than what we do know. What matters the most is developing a critical distance. When you start having doubts, you’re on the right track!

REFERENCES

Dudareva, N., Negre, F., Nagegowda, D.A. & Orlova, I. 2006. Plant volatiles: recent advances and future perspectives. Critical Review in Plant Sciences 25: 417–440.

Endo, H., & Rees, T. D. 2007. Cinnamon products as a possible etiologic factor in orofacial granulomatosis. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal 12(6), 440-444.

Sarrami, N., Pemberton, M. N., Thornhill, M. H., & Theaker, E. D. 2002. Adverse reactions associated with the use of eugenol in dentistry. British Dental Journal, 193(5): 253-255.

Header image: Pixabay

Thank you. Really clear pragmatic and well written. Im a distiller and educator of distillation technique of spirits and aromatics and questions and assumptions always come up. Nice to have a gentle way of presenting an answer withput taking away the magic.

Hello Jill! Thanks for your kind words, I appreciate it. I’ve known your work, and I wish you best luck.

Oh wow, this is exactly what I have been hoping to find. Thank you so much for writing this and posting it. It will truly be helpful to this newbie to essential oils. 🙂

Hi Sheila! I’m glad you find it useful! 🙂

Thank you again for another well written piece Petra. I am becomning fond of your writing as well as your interpretations. Nice to come across like minded individuals as I tend to my own ” weeding out “of relevenat/irrelevant information on essential oils, hydrosols, as well as the art of distillation. 🙂

Thank you, Suzanne. I appreciate your kindness, especially as I’ve just started out with my English blog 🙂

Great Job Petra! Clear, concise & packed full of valuable information!

Glad to help, Kris.

This is such a useful post and should be compulsory read for all students in aromatherapy like me. Thank you very much Petra and please keep posting 🙂

Thank you so much, Maianna! I will keep updating it.

So. Glad. I happened across your site.

Seriously appreciate your well balanced and rational write ups!

You’ve provided a really great avenue for consumers to take a step back and reassess why they’re purchasing what they’re purchasing. Especially appreciate your encouragement of self-pursuit for hard evidence and facts.

Wish there was more of this type of encouragement in the world, all around -_-

Thanks this was a great well written post. One question I had was in reference to where you said it’s ok to put a drop of oil in a jar of honey – can you clarify please as otherwise you were not advocating ingestion – and no quality source I know does – but this is effectively saying it’s ok to eat oil in honey? Thanks, Nigel from New Zealand.

Hi Nigel and thanks for your comment, I’m sorry I somehow missed it entirely! When administering essential oils, it’s all about the dose which defines the balance between safety and efficacy. The example with honey is meant to illustrate culinary use of essential oils where the emphasis is more on flavour and less on the therapy, and the administered doses of essential oil constituents are comparable to eating aromatic herbs and spices with food. The article is written for beginners who are overloaded with information and need basic guidance. That said, I’m not against ingesting higher doses for therapeutic purposes – as long as you know what you’re doing or stick with registered essential oil-based products (such as lavender oil capsules).

Excelente text!